It is July 4th, 2025. The air is thick with the familiar scent of grilled meat and the distant percussion of fireworks—rituals of celebration, of remembrance, of a nation’s birth. Yet, beneath the surface, something else stirs: a sense of finality, of an era closing. The end of the democratic experiment.

Today, the President will sign into law the so-called “Big Beautiful Bill,” a piece of legislation so sweeping, so transformative, that it has become impossible to ignore the sense that the American democratic experiment, began 249 years nearly ago today, has reached its denouement. The irony is not lost on anyone who still cares to notice such things: the date, July 4th, the same day that witnessed the deaths of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, the twin architects of the republic, fifty years to the day after they declared its independence. The experiment began on a July 4th; it ends, it seems, on another.

It is difficult to overstate the ambition—or the audacity—of the “Big Beautiful Bill.” It is a legislative monolith, a monument to a particular vision of America, one that prioritizes the consolidation of power, the privileging of the already privileged, and the dismantling of the social contract that, for generations, bound Americans together. The bill makes permanent the tax cuts of 2017, slashes funding for Medicaid and food assistance, and pours unprecedented sums into defense and border security. It raises the debt ceiling by trillions, guts clean energy incentives, and imposes new hurdles for those seeking public assistance. It centralizes federal authority in ways the founders would have found unimaginable, overriding state regulations and concentrating power in the executive branch. And it does all this with breathtaking speed, through procedural maneuvers that shut out dissent and silence debate.

There is a certain grim poetry in the way this has unfolded. The bill passed by the narrowest of margins, every Democrat opposed, the Vice President casting the deciding vote. Polls show a majority of Americans disapprove, but the machinery of government grinds on, indifferent to the will of the governed. The very mechanisms designed to protect minority rights—reconciliation, limited debate—have been twisted to serve the opposite end: the imposition of a minority’s will on the majority. The social contract, always fragile, now lies in tatters.

It is tempting, in moments like this, to reach for the language of the founders, to recall the ideals they set forth in Philadelphia in 1776: government by consent, the primacy of liberty, the promise of equality. But those words ring hollow now, echoing in a chamber that has been emptied of meaning. The democratic experiment was always just that—an experiment, uncertain, provisional, subject to the whims and passions of its participants. Today, the results are in.

And yet, the symbolism of the date refuses to be ignored. July 4th, that most American of days, already bears the weight of history. It was on this day, in 1826, that Adams and Jefferson—rivals, collaborators, visionaries—died within hours of each other, their lives bookending the first fifty years of the republic. Adams’ last words, “Thomas Jefferson survives,” were mistaken; Jefferson had died earlier that morning. The coincidence has long been read as a sign, a kind of cosmic punctuation mark on the founding era. Now, nearly two centuries later, another July 4th marks another ending.

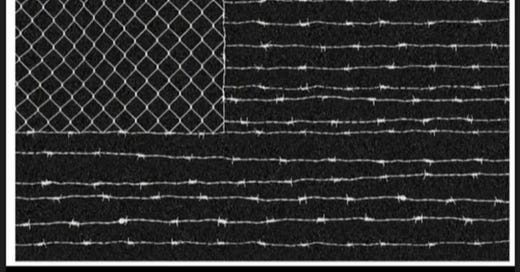

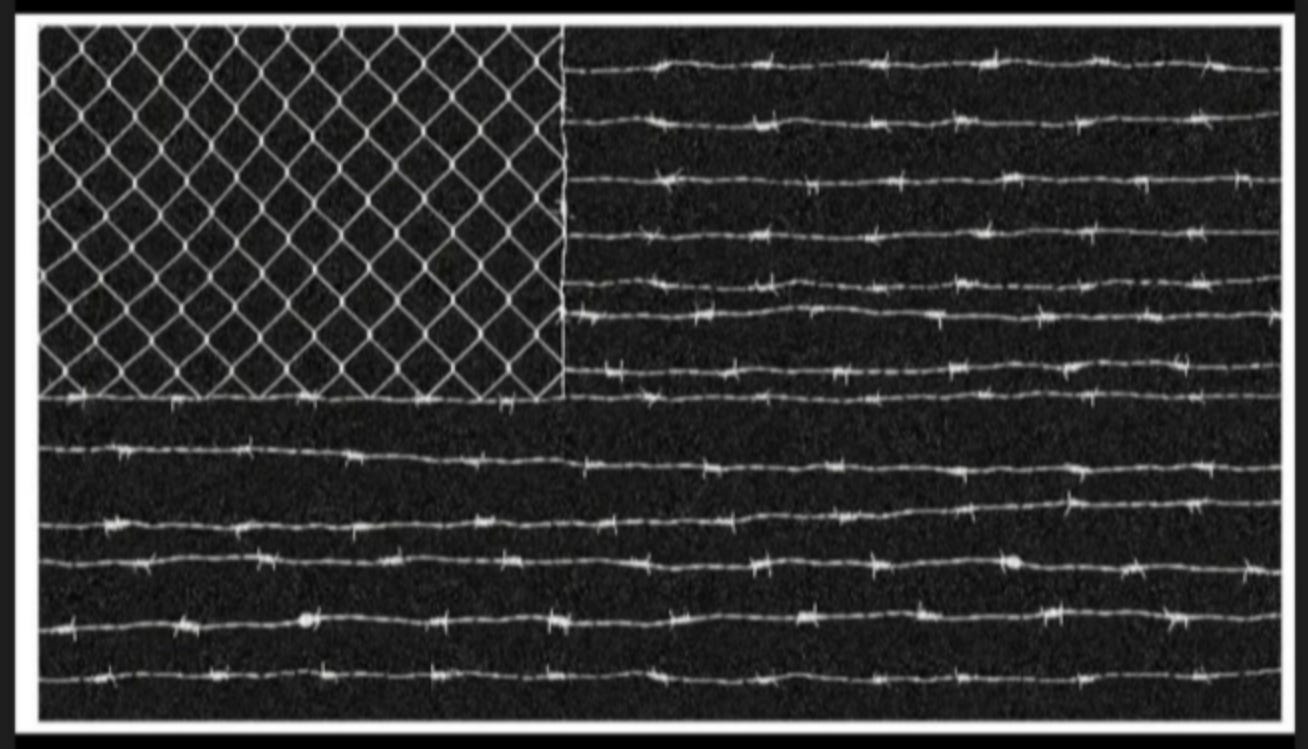

There is a cruel symmetry here. The nation that began in rebellion against concentrated power now embraces it. The republic that once prided itself on its messy, participatory democracy now seems content with rule by fiat, by the few for the few. The social safety net, painstakingly woven over generations, is unraveled in a matter of days. The promise of equal opportunity is replaced by the reality of entrenched privilege. The machinery of government, once a tool for collective action, becomes an engine of exclusion.

What, then, are we to make of this moment? Is this truly the end, or merely another chapter in the long, tumultuous story of American self-government? History is rarely so neat, so accommodating to our need for narrative closure. But it is hard to escape the feeling that something essential has been lost, that the experiment has run its course. The fireworks will still explode tonight, the flags will still wave, but beneath the spectacle, a quieter truth asserts itself: the democratic experiment, begun in hope and daring on a July 4th long ago, has ended on another, in a flurry of signatures and a cloud of irony.

Perhaps, in time, another experiment will begin. Perhaps the spirit of Adams and Jefferson, of those who believed in the possibility of self-government, will survive this moment, as Adams believed Jefferson survived him. But for now, on this July 4th, we are left with the knowledge that the arc of history does not always bend toward justice, and that even the boldest experiments can fail.

Only through the minds of radical leftists. Give us your plan to fix the country. More government dependency I suppose.